FUI-Bloggen

FUI är förkortningen för forskning, utveckling och innovation. I FUI-bloggen skriver Yrkeshögskolan Novias personal om sitt jobb, forskning, projektverksamhet och andra betraktelser.

Blogginlägg som är granskat av Novias redaktionsråd är utmärkta med nyckelordet "Granskat inlägg".

Vi följer CC-BY 4.0 om inget annat nämns.

Undervalued Skilled Migrants in Finland

Geoffrey Pororo, MBA Service Design, Novia University of Applied Sciences

Reija Anckar, Ph.D. (Econ.) Head of Master’s Degree Programme in Business, Service Design at Novia University of Applied Sciences

Undervalued Skilled Migrants in Finland- Dialogue and Potentialities through Novia UAS School of Business

The Finnish society today is undergoing massive transformation due to aging demographic amongst the working population. This is not mere political propaganda. Substantial research from different quarters has collectively affirmed the trend that Finland is indeed, the fastest aging society in Europe, much ahead of its Nordic peers. In fact, the demographic shift is happening so rapidly that according to United Nations, Finland ranks among the top five fastest aging societies globally. As of the year 2019, at least 22% of the population in Finland was 65 years of age or older and is expected to spike to a stunning 28% by 2050. This transformation has a direct bearing on the sustainability of the Finnish labour market. The real question to answer in such instance is - how will Finland fill in the existing labour shortfalls to ensure that government tax coffers remain healthy enough to substantially maintain the welfare state? It looks like the halcyon days are about to become only a story to reminisce upon. The very notion and die-hard affinity to homogeneity as a totem pole for Finnish success is being subjected to the test of time. Multiculturalism and diversity are now needed as a new mantra for competitiveness.

Juxtaposed to the just described scenario, Finland is already currently struggling economically relative to its neighbours. Ever since the fall of Nokia from grace in the global mobile telephony market, the country has struggled to produce high-growth, high-impact global businesses that can sustain the economy. Nokia for instance, used to pump-in (during its heyday) the equivalent of 3.5% of the country’s GDP in terms of its revenue. This created enough buffer to drive ahead the Finnish economy, anchoring long term economic plans for the country. Life at the time was great and optimism about the future was ubiquitously evident . Today, with skyrocketing inflation and vertiginously high global food prices, young Finns are technically earning lower than their parents. It looks like Finland must do more to reverse its virtues.

In view of the above, the drive over the last couple of years to heighten labour-based migration gained significant momentum. We have recently seen changes in immigration regime to allow for increase in education and labour-based migration. This was a first, given Finland as an inadvertently closed society with a garish background of stringent immigration. The main immigration strategy appears to be anchored primarily on education-based immigration. Such is the fulcrum onto which Finnish government hopes to attract skilled migrants into Finland through a study pathway. Ideally 3 in every 4 of the skilled migrants cum students would be retained within Finnish borders after completing their studies. This way talent can be perennially channelled into the Finnish labour market to relief both the existing and the projected labour market shortfalls.

It is envisaged that international students target is to be tripled to 15 000 new foreign university and polytechnic/UAS students by the year 2030. The Finnish National Agency for Education estimates that the number of students with immigrant or foreign background studying at Finnish higher education institutions more than doubled between the year 2010 and 2020. It is worth highlighting this scale of increase further. In 2010 the report reveals, the number of students in Finnish higher education institutions, who were not Finnish citizens, was 8500 compared to about 17 500 in 2022.The above figures represent an astounding 51.4% increase in foreign student influx over a twelve-year period. In effect this means that the number of foreign student population in Finland is at the date of this article growing at an annual average of about 4.3% against the average annual Finnish population growth of about 0.3%. This latest influx of migrant talent can, therefore, not go unnoticed.

How is Finland receptive of this emerging talent?

Whilst efforts from the Finnish government to attract the above talent into the Finnish borders, are bold to say the least, the impetus at a broader scale for now remains to be pure political rhetoric. In the dynamic landscape of the Finnish labour market, skilled migrant talent is unceasingly subjected to unwarranted barriers. Highly skilled migrants are undervalued. This massive talent is often so adamantly dismissed by the Finnish employers. What is the problem? Why is there a disparity between what the Finnish government sees as a solution for the future and the general appetite from employers?

There appears to be a prevalent mindset within the Finnish society that metaphorically asserts that it’s got to be Finnish to be real kaura. It is ironic how migrants who have been highly trained by the same education system Finland is reputable of, are relegated to the fringes as litter-bin pickers, janitors, and bus drivers. Is this in a way a self-declared vote of no confidence in the same education system the world has come to trust? If skilled migrants are exposed to the same education offered to the Finns, why is there even a shadow of doubt about their ability to adapt in the Finnish labour market? It is not uncommon to see a master’s or a doctorate degree holder doing the just stated menial jobs. Surprisingly a great percentage of these skilled migrants would have worked in global companies elsewhere before coming to Finland. Quite to the contrary this experience means nothing once they are in Finland. Just how does an individual who worked for years at Coca-Cola somewhere in South Africa, Nigeria, or Brazil as an example, fails to successfully perform when they suddenly work for a micro-brewery in the corner of Oulu?

The prevailing labour market rejection isn’t even about skilled migrant talent obscured by its origins from the so-called Third countries. Equally competent migrants from other Western nations do not see the light of the day in Finland. The issue of language proficiency has been suggested as a hindrance. However, investigations have shown that migrants, who have been brave enough to learn the language, are not finding it any easier either. This is a very falsified posture on the side of Finnish employers that delays progressive imagination around the problem at hand. There is a background to Finland’s sense of discrimination even though in some circles it is touted as a place of equal opportunity and respect for human rights. The pockets of history are well-lined with instances of Finland as a very fragmented society that operates across nationalistic lines.

There is an urgent need to evolve Finland into a highly inclusive society that recognises the worth of everyone. Diversity everywhere except in Finland is seen as a socio-economic asset . In fact, research has consistently proven that organisations that have deliberate mechanisms to diversify their workforce, have often come out top in terms of their competitiveness and capacity to innovate, relative to their less diversified counterparts.

Solutions through the Thesis Journey of Geoffrey Pororo

Geoffrey Pororo endeavoured passionately to come up close and personal with the current problem through his MBA thesis in Service Design. He needed to understand the nature and the breadth of the skilled migrant rejection in the Finnish labour market. This way optimal solution could be created on how the problem may be rectified. Geoffrey started off by spending hours on what turned out to be very wide literature sources, investigating the dynamics of social exclusion among the skilled migrants in the Nordics, and by extension Finland. Alongside this secondary research expedition, empirical research was undertaken to corroborate preliminary findings sketched out from literature search. The empirical study involved three distinctive research methods to enable a sense of triangulation in the findings.

Exploratory Interviews - At first expert interviews were undertaken with key authorities in the area of migrants and the Finnish labour market. Background information from the literature study was used to inform the approach and focus to semi-structured questioning, allowing also for more directed probing and follow up.

Feedback from the expert interviews pointed out four stumbling blocks to the uptake of skilled migrant talent in Finland. Just to narrate a couple of these impediments: The interviewees touched on the issue or “Relational Serendipity” in which they believed people to have natural predisposition to appreciating the fluidity of conversations in their socialisations. In this sense language proficiency becomes key. Any person who tends to obstruct this free motion is somewhat naturally at a disadvantage and risks being excluded as an intruder. Given that Finland has for quite a long time been doing very well operating in Finnish and Swedish languages, a person, no matter how skilled, who is seen to alter conversations in the coffee room is often viewed with disdain.

Secondly, the interviewees indicated “Cultural Disposition of Mistrust” among the Finnish society that is not easily open to those coming from outside. In a labour market driven by referrals and personal connections, it follows that skilled migrants struggle for a long time, to get recommendations for potential employment as their social circles are limited, if any at all.

Thirdly, the interviewees indicated the Finnish society to be driven by a great deal of privilege in which the Finns have options to take or to not take jobs that exist at the bottom of the value chain. The jobs are physically demanding in nature, and it has become a cultural paradigm that such are for migrants. In this sense migrants, even those who are highly skilled, are not seen to belong to any other form of employment than that which is exclusionary. Lastly, the interviewees pointed out the need for skilled migrants to understand how to highlight their core differentiators in a competitive European labour market. They are competing with those that have track record in a landscape known to employers. In order to be recognised as worthy, a skilled migrant must appear to be truly head and shoulders above.

The above findings were then compared with responses from general qualitative survey elucidated through verbal anecdotes from skilled migrants who were probed during several job seeking mentoring sessions held in Turku. Here again, semi-structured face-to-face interviews were used to drive group conversations around the issue based on responses given during individual survey. In conveying the experiences, they encounter in their process of job seeking, skilled migrants narrated three key themes they perceive about the nature of the Finnish labour market. Firstly, they believe that their lack of employment opportunity is an act of powerplay, in which the Finns do everything possible to deny them access. They do not want migrants to become too powerful in their own country, and hence relegating them to the types of employment that pays very little to earn substantial living. Secondly, skilled migrants viewed the Finns as somewhat conceited and overly dismissive in the capability of anything that is not Finnish. They asserted that to be an attitude that needs to change instead of putting lack of language proficiency at the fore.

Immersion Research – This research method was executed in form of autoethnography. Geoffrey Pororo took up a job in the cleaning sector to understand the daily issues skilled migrants must go through. A diary of epiphanies was created over a period of eighteen weeks. Key themes were extracted from these findings. The discoveries, which potentially kept skilled migrants dissatisfied in these types of exclusionary employment ranged from the physical nature of the jobs, routine and repetitively manual tasks that demand very little thinking, to often poor empathy among the managers. Workers in this instance are seen as tools of contract delivery than human beings with aspirations coordinated within worthy social contexts shared by everybody else.

Netnography – This was the final research method in which Geoffrey Pororo covertly joined migrant Facebook groups in Finland to discover topical themes skilled migrants go through in their job seeking efforts. The idea of constant rejection still resurfaced, with the majority except those who might be married to a Finnish partner, thinking of leaving the country. There is general anger among the skilled migrants in Finland bleeding emotionally due to lack of chance amid apparent opportunity.

In view of the above, the issue of labour market rejection in Finland is very complex, driven by several systemic factors. It is for this reason that there isn’t any silver bullet in how it ought to be resolved. However, little contributions from all angles and all interested parties can collectively bring us closer to progress. Pororo’s thesis was therefore, about finding a way of putting his little drop in the bucket.

Personally, Geoffrey Pororo represents a typical skilled migrant in Finland. He has about 20 years of work experience working for both global and national companies in his home country across various sectors. He got his education in both the US and the UK. His current MBA programme was his second master’s degree. In his working life, Pororo never had to do what he was not trained for due to lack of opportunity in one way or the other. That is why it was critical that he , therefore, experience directly how it feels to be a subject of exclusionary employment once he arrived in Finland. This was to get direct insights of the crude realities skilled migrants like him experience.

As Geoffrey Pororo navigated through this eye-opening experience, it sufficed to conclude that the Finnish recruitment system, unfortunately, leans towards nationalist sentiments rather than credible competencies. The system is mostly opaque, relying on word-of-mouth recommendations than on proven competences established through a systematic process. Such a process would allow everybody irrespective of their cultural background to be given an equal chance. In a situation, where skilled migrants have very limited social cycles; they never get to be recommended by anyone. In fact, as high as 80% of job vacancies in Finland are hidden. In such scenario, highly credible skilled migrants find themselves in roles that don't align with their qualifications, creating an economic harness that hinders the country's growth potential. But in the eyes of the recruiters that really doesn’t matter. They are Finnish and they feel more comfortable recruiting purely Finnish people.

What are the Implications?

Apart from the lost opportunity to bring back the economy of Finland into a sustainable growth curve, Finland is busy brooding a parallel society. A highly sophisticated section of the Finnish intelligens is being downplayed and dismissed nepotistically as irrelevant. This, in Geoffrey Pororo’s opinion, is a recipe for impeding disaster. The chicken will soon come home to roost! If you really want to invite trouble into a society, the best way to achieve that is to make some of its highly educated members more than desperate. The social pain of being constantly rejected in a society has been confirmed by psychologists to be having the same neurological footprint as physical pain. In a way, the type of rejection skilled migrants currently experience in Finland has the same neurological aftermath as direct physical abuse. Researchers have also confirmed that a rejected member of the society is an angry individual. The recent demonstrations in France that resulted in massive damages in infrastructure are a typical example of accumulated frustration now being released like pressurised gas.

What makes the above situation worse is the continued government rhetoric that still sells Finland outside as a country that has plenty of jobs and open to international talent. The dichotomy between this narrative and actual experience inland is potentially damaging to the national reputation of Finland. It also has negative impact on the business continuity of the academic institutions of higher learning in the country, which lately have had to make costly adjustments to accommodate an influx of i skilled migrants in form of international students. In Geoffrey Pororo’s research as high as 40% of the student population interviewed concerning their experience in Finland are prepared to go back to their country upon completion of their studies. This is in line with discoveries from the Netnography extracted themes in “foreigners in Finland” social media groups. The students feel cheated and compromised. They believe now that their move to Finland is a failed experiment, they have no future in the country, are happy to head back to their respective countries and start everything afresh. This finding is consistent also with research carried out by other researchers in Finland recently. Only less than 10% feel that irrespective, they would like to still stick around and probably pursue the entrepreneurial route.

The above revelation led Geoffrey Pororo to delve into a groundbreaking Service Design concept to provide necessary intervention to the anomaly. In order to understand if the right problem was being solved in the first place, service design tools and methods were then deployed alongside empirical discovery. One of such tools was the use of user personas to create a mentally tangible context for the problem to be solved. The user personas segmented the users into definitive groups that are to be targeted with the new service design solution. Once the user groups were identified customer journey coupled with empathy mapping were used to help frame the gist of the problem to be solved. Finally, user stories were created to provide a vivid reminder of what problem is there to be solved, for whom, and why. It is quite easy for the real issue to get lost in the intellectual shaffle unless there is constant reminder of what is it that is being solved. With these user stories, co-creation sessions were held with skilled migrants to develop skeletal solutions for the problem concerning skilled migrant talent utilisation in Finland. The rest of the development was executed tactically with other design resources, with service design process strategically providing leadership oversight to the development process. This way the right creative synergies that harness the imaginative foresight of users and existing design competences beyond the capabilities of the service designer can be angled towards optimally resolving the problem.

The service design idea is aimed at not only addressing the impending economic disparity, but also as demonstration that Novia School of Business is strategically placed (in view of the prevailing circumstances) to bridge the gap between academic excellence and entrepreneurial pulse of Finland. It will be a long time before Finnish employers change their mindset towards skilled migrant talent. An ideal opportunity at this juncture is to optimise the potential influence of the School of Business in becoming a breeding ground for potential skilled migrant entrepreneurs, who come into the school to further their education.

The Service Design Solution

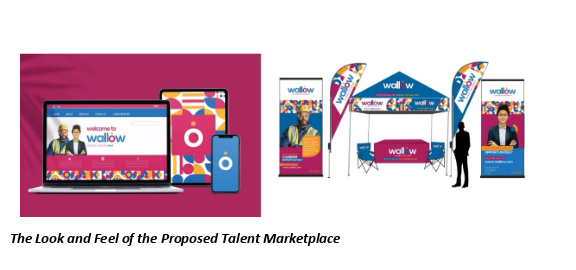

The concept proposed is a digital talent marketplace named Wallow. It is designed to match skilled migrants with one-time project opportunities within key organizations. The goal? To transition this engagement into long-term, fulfilling careers. Here skilled migrants from innovation-driven vocations such as designers, engineers, marketers, communications specialists, and storytellers get to upload their resumés and portfolios into this AI and Machine Learning based platform. The reason innovation led vocations were chosen relative to others is because, unlike other general professionals, these ones often must have tangible proof of their talent on and above their CV. Such comes in the form of a portfolio of works or in case of software developers, a repository of sorts. If talent is showcased in this manner, bias can hopefully be minimised. For example, the works of a great designer will always hit the recruiter right on their face and make them feel bad to not consider such a talent.

But just what is it that will compel employers to disclose their projects for the talent they do not value in the first place? The platform uses AI and Machine Learning to review project goals from these employers, objectives, and innovation requirements. It matches these to the integrity and skill sets of the inhouse project team (mostly Finnish professionals). The system then identifies talent irregularities within the suggested project team. The platform would consequently use skilled migrants to fill in those gaps. In this instance, employers will conveniently frequent the platform to test the robustness of their teams against project goals. Once the holes have been clearly punched by the AI engine, the system opportunistically trickles in the skilled migrant talent as potential remedy. Meanwhile the evidence for this talent is there in the form of a tangible portfolio and that forms the basis from which to start negotiating with the employers to trial this talent on a given one-time project. Once the skilled migrant has proven their capability, (and in most cases they will), the employer must judiciously commit to transitioning the relationship into formal employment.

Wallow in this instance operates at the intersection of talent acquisition and innovation capacity building for Finnish companies. With changing demographics in Finland as already illustrated earlier, innovation will remain the most critical corporate activity the country will need to rely on to change its declining virtues. Innovation is where diversity in thinking and perspectives is key, and what area is more ideal to lull in skilled migrant talent than this one? Wallow, therefore, is a trial ground, where Finnish employers can test, evaluate, and adopt skilled migrant talent in a risk mitigated mode. In the end everybody emerges a winner.

In Geoffrey Pororo’s thesis journey he collaborated with Business Turku (formerly Turku Business Region). With this idea he was privileged enough to be admitted in their 10-week business acceleration programme. In this intensive bootcamp, the idea was refined to make it fit enough as a proper business concept. Such approach showed the power of seamlessly mash mellowing academic insight with real-world business sensibilities.

This initiative, far from being an isolated academic exercise. It is a testament to the potential transformative power our business school has in seeing through skilled migrant talent into the Finnish entrepreneurial landscape. But why is this more than just a noble pursuit? If our business school can develop a deliberate mechanism for interfacing skilled migrant talent yield it harvests every year with the Finnish entrepreneurial ecosystem, acting as a filter and siphon for this talent, such will not just be a passive social responsibility; it's a strategic move.

Novia UAS School of Business has an Opportunity to Recraft the Narrative

In an age where universities are not just ivory towers but active contributors to societal progress, Novia University of Applied Sciences’ School of Business can distinguish itself by actively participating in the dismantling of undue social barriers skilled migrants go through. It will be an intelligent expedition, which can reinforce future alumni networks that hold sufficient economic power to better utilise future skilled migrants in an environment that currently rejects them. This will be a clear market differentiator for the school. It can signal to prospective students, faculty, and industry partners that the school is not merely an institution of academic learning but an active ingredient catalysing the future of Finnish society and the nature of its workforce.

The above approach aligns well with increasing expectations for universities to go beyond their academic role into driving real-world impact. Such posture can enhance the school’s reputation and appeal in an operational environment where the odds are against Finnish academic institutions. The word is currently out that there is nothing for skilled migrants in Finland- that they are better off staying in their home countries. Novia UAS School of Business can in this instance be the only beacon of hope for international students aspiring to make it in Finland, taking advantage of the school’s intellectual and social infrastructure for meaningful mobilisation of skilled migrant talent from its graduates. Such will not just happen, however. Mechanisms need to be put in place and resourced now to bring that endeavour into reality.

More detailed thesis publication and the research journey can be found at: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-202401011001.

The blogpost has been reviewed by Novia's editorial board and accepted for publication on 17.1.2024

![]()

FUI-Bloggen

Blogginlägg som är granskat av Novias redaktionsråd är utmärkta med nyckelordet "Granskat inlägg".

Vi följer CC-BY 4.0 om inget annat nämns.

Ansvarsfriskrivning: Författaren/författarna ansvarar för för fakta, möjlig utebliven information och innehållets korrekthet i bloggen. Texterna har genomgått en granskning, men de åsikter som uttrycks är författarens egna och återspeglar inte nödvändigtvis Yrkeshögskolan Novias ståndpunkter.

Disclaimer: The author(s) are responsible for the facts, any possible omissions, and the accuracy of the content in the blog.The texts have undergone a review, however, the opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Novia University of Applied Sciences.

Posta din kommentar

Kommentarer

Linwoodcigma 20 feb. 2026 12:42 (2 dagar sen)

Iver Therapeutics: <a href=" http://ivertherapeutics.com/# ">stromectol south africa</a> - Iver Therapeutics

Leonardcef 20 feb. 2026 12:39 (2 dagar sen)

Iver Therapeutics <a href=http://ivertherapeutics.com/#>Iver Therapeutics</a> ivermectin 2%

LarryExcuh 20 feb. 2026 11:57 (2 dagar sen)

order zoloft: <a href=" https://sertralineusa.shop/# ">zoloft pill</a> - zoloft no prescription

TracyBow 20 feb. 2026 10:12 (3 dagar sen)

http://ivertherapeutics.com/# ivermectin 10 ml

Linwoodcigma 20 feb. 2026 09:35 (3 dagar sen)

Neuro Relief USA: <a href=" https://neuroreliefusa.shop/# ">Neuro Relief USA</a> - Neuro Relief USA

ElvisShamn 20 feb. 2026 09:26 (3 dagar sen)

canadian pharmacy world coupons <a href=" https://maps.google.co.mz/url?q=https://smartgenrxusa.shop ">online pharmacy 365 pills</a> or no rx pharmacy <a href=" https://www.ydmoli.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=3403 ">onlinepharmaciescanada com</a>

http://haedongacademy.org/phpinfo.php?a<>=wall+decor+decals+(<a+href=https://smartgenrxusa.shop:://bluepharmafrance.com/blogs/interior-design-review/hashtag-interior+/> best online thai pharmacy or http://www.ktmoli.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=429710 on line pharmacy

<a href=https://cse.google.am/url?sa=t&url=https://smartgenrxusa.shop>canada rx pharmacy</a> compare pharmacy prices and <a href=http://bbs.51pinzhi.cn/home.php?mod=space&uid=7660600>legitimate canadian pharmacies</a> thecanadianpharmacy

LarryExcuh 20 feb. 2026 07:56 (3 dagar sen)

generic zoloft: <a href=" http://sertralineusa.com/# ">generic for zoloft</a> - generic for zoloft

TracyBow 20 feb. 2026 07:28 (3 dagar sen)

http://smartgenrxusa.com/# Smart GenRx USA

Glennfit 20 feb. 2026 07:20 (3 dagar sen)

http://smartgenrxusa.com/# Smart GenRx USA

Linwoodcigma 20 feb. 2026 06:30 (3 dagar sen)

canadian pharmacy meds review: <a href=" https://smartgenrxusa.shop/# ">bitcoin pharmacy online</a> - Smart GenRx USA

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 nästa »

Inga har kommenterat på denna sida ännu