Bioekonomi

I bloggen Bioekonomi får du veta mer om Yrkeshögskolan Novias forsknings-, utvecklings- och innovationsverksamhet inom forskningsområdet systemomställning för att bygga resiliens. Majoriteten av personalen finns huvudsakligen i Raseborg. Här bildar forskare, projektarbetare, lärare, studerande och administrativ personal en dynamisk helhet. På vår blogg kan du läsa om vilka vi är, vad vi gör och om våra resultat. Välkommen!

Vid frågor eller feedback kontakta bloggens administratör Heidi Barman-Geust (Heidi.barman-geust(a)novia.fi)

Vi följer CC BY 4.0 om inget annat nämns.

Systemic Transformation to Build Resilience is one of Novia University of Applied Sciences six' research areas. The activity is mostly located in Raseborg, in southern Finland. As a dynamic unity, our researchers, project workers, teachers, students and administrative personnel produce versatile results in research, development and innovation. We blog about who we are, what we do, what our conclusions are, and how we implement them. Welcome!

If you have questions, please contact Heidi Barman (Heidi.barman-geust(a)novia.fi)

We folllow CC BY 4.0 if nothing else is stated.

Why climate action is not firefighting, and inaction ignites a vicious cycle

The 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (30th Conference of the Parties—COP30), the annual global Climate Summit where countries negotiate actions to tackle climate change, concluded in Belém, Brazil, at the end of November 2025. Many welcomed the news of a consensus reached among the parties (the participating countries) in celebration, seeing it as proof that the multilateral process remains alive. Yet, this could also be interpreted as a sign that, in our increasingly polarised and fragmented world, we have lowered the bar to the point where any agreement is considered a “victory.”

In truth, the outcome appears to be mixed. On the one hand, perhaps the greatest achievement is that wealthier nations agreed to boost financial aid to low-income countries, specifically to triple adaptation finance to at least USD 300 billion annually by 2035, within a broader pledge to mobilise USD 1.3 trillion per year for climate action by 2035. On the other hand, however, the greatest disappointment is the omission of a commitment to transition away from fossil fuels and to include a roadmap for doing so, as well as for halting and reversing deforestation (the two essential drivers of climate change). In fact, the final agreement had no mention of fossil fuels, a battle seemingly won two years earlier at COP28. And while Brazil pledged to develop these roadmaps independently, these will take place outside the formal UN regime, and as such, carry significantly less weight. Which countries opposed a roadmap to phase out fossil fuels? Were they oil producers concerned about the consequences for their economies, still heavily dependent on fossil fuel exports? And/or developing countries worried that financial aid pledges might not materialise, while restrictions on fossil fuel use could undermine rapid energy access and short-term poverty alleviation? And/or perhaps countries influenced by the large numbers of fossil fuel lobbyists, who continue to outnumber nearly all country delegations? To this day, there is no clear answer as to which countries oppose and why. But it would have been enough for any one country to oppose for the roadmap not to be included in the final agreement, since COP decisions are adopted by global consensus, meaning no formal objection by any party. Distinct from other historic global conventions (such as the Montreal Protocol, which successfully regulated global emissions of ozone-depleting substances), the requirement of consensus is a distinctive feature of climate negotiations intended to generate broad support for climate agreements; yet, in reality, it has mainly guaranteed weak outcomes and slow progress.

Notably, during the event, the negotiations were briefly disrupted when a fire broke out on the premises. Thankfully, there were no serious injuries, as people were quickly evacuated, and the blaze was brought under control. Reports highlight how first responders acted swiftly and participants collaborated to manage the emergency. One cannot help but notice the irony and contrast: would first responders ask negotiators to hold discussions on a framework to agree—by consensus—on the need to evacuate based on voluntary actions? Absolutely not. First responders understand that they must act quickly and decisively to save lives. This comparison is not intended to downplay the complexity and seriousness of climate diplomacy, nor the commitment and hard efforts of many negotiators. Rather, to highlight the stark contrast between how rapidly we mobilise in the face of tangible emergencies and how slowly we are responding to the equally life-threatening climate emergency. This analogy invites further exploration by contrasting core principles of firefighting with the dynamics of climate action (or more precisely climate inaction) as shown below:

|

Firefighting principle |

Climate (in)action |

|

1. Identify the threat (fire) quickly and act immediately; hesitation can cost lives. |

While we identified the threat of climate change decades ago, we allowed denialism to take hold, debated whether the “flames” are severe enough to warrant decisive action, and ultimately made response to it voluntary and optional, acting as if there is still time, even when entire regions burn, flood, and key Earth system processes face the risk of irreversible change. |

|

2. Alert everyone and call for help, bringing in those more equipped to respond. |

Rather than acting collaboratively according to their capacity to respond (doing the most to control the crisis), the majority of countries have prioritised competition (doing as little as possible while expecting others to shoulder the burden). Those with significant technological and financial resources have particularly fallen short, and debates have largely centred on responsibilities rather than on the capacity to act. |

|

3. Use the right tool as soon as possible (e.g., extinguisher, blanket). The correct tool used quickly can extinguish the fire. |

While tools exist, such as renewable energy technologies, policies to curb deforestation and high-carbon lifestyles, and climate finance, their implementation has been marginal. Instead, our collective focus remains on growing our economies, which still extensively rely on fossil fuels, allowing emissions to continue rising (thus “spreading the fire”), in the hope that a future tool (such as atmospheric carbon capture or geoengineering) will one day reverse the effects of today’s inaction. |

|

4. Attack the fire at its base, not the flames, and remove any sources of fuel.

|

Negotiations continue to focus on reducing emissions without clear roadmaps for phasing out fossil fuels, halting deforestation, transforming food production systems, and modifying diets and lifestyles. This approach, recently articulated by Saudi Arabia’s deputy environment minister as “the issue is the emissions, it’s not the fuel”, is like attacking the flames while deliberately adding fuel to the fire (planning to expand fossil fuel production). |

|

5. Have a clear exit and be ready to retreat if the fire grows uncontrollably. |

There is no exit from the planet. And aside from a few billionaires’ ideas about colonising the Moon and Mars, visions that are neither realistic solutions nor desirable alternatives for the whole of humanity, there is no way out if climate change gets out of control (a “Hothouse Earth” or worse). |

|

6. Never re-enter a burning building. Find another route. |

After every climate disaster, millions have no choice but to return to their climate-stricken homelands, except for low-lying island states and other regions projected to become uninhabitable. Meanwhile, countries continue to “re-enter” the same weak frameworks and voluntary measures that are failing. |

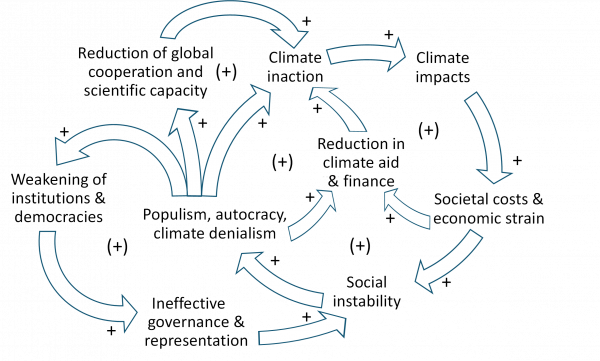

It is clear that climate action is not firefighting. What is worse, while we might assume that as climate impacts intensify, we will, once and for all, scale up our mitigation efforts to keep climate change under control, the opposite may occur. Climate inaction drives more severe climate impacts resulting in substantial societal and economic costs, including damage to critical infrastructure, food and water insecurity, loss of lives, and broader economic strain. When governments fail to implement rapid and effective responses—whether due to institutional weaknesses, limited capacity, or political gridlock—societal instability increases. These pressures, combined with the inability of established political parties to represent their constituents and address their needs, create fertile ground for the rise of populist and autocratic leaders. Many such leaders, particularly far-right and divisive nationalist figures, promote climate denialism, eventually rolling back climate policies and further undermining meaningful climate action. In addition, as domestic priorities shift—whether due to economic strain or the agenda of climate-denying governments—climate aid and finance are reduced, weakening global climate action. Moreover, nationalist and autocratic leaders tend to diminish international cooperation and hinder key multinational scientific collaborations (including Earth-science, which is fundamental to planetary thinking), both of which are critical for effective climate action. Lastly, these leaders often weaken democratic institutions and democracy itself, undermining their capacity to respond to crises and thereby exacerbating societal vulnerability. It is, perhaps, an additional irony that in seeking global consensus in climate negotiations (ostensibly to uphold democratic values of inclusiveness and equality) we may not only be compromising ambitious climate action but also inadvertently putting democracies at risk. Hence, a good reason to reconsider the emphasis on consensus.

All these relationships illustrate how climate inaction can ignite systemic feedback loops that perpetuate social instability and reinforce further climate inaction; a serious “derailment risk” of climate action, meaning that failing to act now significantly reduces the prospects of acting in the future. This dynamic, combined with amplifying natural climatic feedbacks that are also at critical risk of being set in motion by inaction, can profoundly disrupt our social-ecological systems. Of course, it does not have to be this way. The same system could reinforce a virtuous cycle if we significantly reduce its risk factors, most importantly by strengthening climate action.

After 30 years of Climate Summits and a decade since the Paris Agreement (COP21), global greenhouse gas emissions are still rising. This indicates that we have failed to recognise climate change as a crisis, let alone an emergency, and act accordingly. And while we tend to use the terms “crisis” and “emergency” to describe it, we do little to offer transformative solutions that tackle the source of the problem in a way that is grounded in common values and ideas of human well-being, merely treating it as a bureaucratic and technocratic issue (yet another factor that seems to make climate a populist issue). Effective and decisive climate action, therefore, requires acknowledging the deep consequences of inaction and mobilising us (especially world leaders) to feel as responsible and empowered to act as firefighters and first responders do.

At Novia University of Applied Sciences, we apply systems thinking to analyse and model energy transition pathways.

The blogpost has been reviewed by Novia's editorial board and accepted for publication on 15.12.2025![]()

Bioekonomi

Blogginlägg som är granskat av Novias redaktionsråd är utmärkta med nyckelordet "Granskat inlägg".

Vi följer CC-BY 4.0 om inget annat nämns.

Ansvarsfriskrivning: Författaren/författarna ansvarar för för fakta, möjlig utebliven information och innehållets korrekthet i bloggen. Texterna har genomgått en granskning, men de åsikter som uttrycks är författarens egna och återspeglar inte nödvändigtvis Yrkeshögskolan Novias ståndpunkter.

Disclaimer: The author(s) are responsible for the facts, any possible omissions, and the accuracy of the content in the blog.The texts have undergone a review, however, the opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Novia University of Applied Sciences.