Bloggar

Local food and fibres in Iceland: more than smelly shark and sweaters

When you mention Iceland, and more specifically food and clothing, people often associate to the smelly, fermented shark and woolen sweaters. In September I had the opportunity to visit Iceland with an Erasmus scholarship and see for myself. I made the trip together with my colleague Heidi Barman-Geust, in order to learn about sustainable food systems and local economy. As the Local Economy team, which I lead at Novia, has several projects related to natural fibres, this was also one field of interest during the trip.

Wool and sheep everywhere

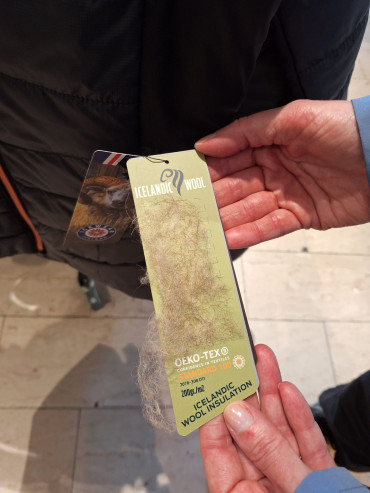

The most obvious natural fibre to study in Iceland is of course sheep wool. During the pandemic Finnish knitters went crazy for Icelandic yarn and the beautiful patterns of the traditional woolen sweaters. After a walk in downtown Reykjavik, the conclusion is that several stores sell sweaters, but only a few of them have those that are hand knitted in Iceland. One example is the Handknitting Association store. These sweaters are priced around 250 – 450 euros. Those that are knitted in China, from Icelandic wool and with Icelandic design are significantly cheaper. Except for in hand knitted sweaters, mittens, hats, blankets etc., wool is present in many other products. There are machine-knitted clothes and blankets, and felted decorations. Some of the most interesting products we saw were ICEWEAR: s outdoor jackets, which are filled with Icelandic wool, instead of down or synthetic materials. According to the company’s webpages, they use Icelandic wool also in knitted goods, produced in the factories on various locations in Iceland.

Icelandic wool insulation in jackets. Photo: Ulrika Dahlberg

Driving northward from Reykjavik, the Icelandic sheep, from which the wool comes, are present everywhere along the roads. Despite this, we learned that sheep production is declining, as it does in many other European countries. Katharina Schneider from the Icelandic Textile Center in Blönduós, tells us that wool is also here a by-product from meat production. Most farmers sell their wool to Istex, which is the largest manufacturer of Icelandic yarn in the country. The company processes about 99% of all the wool in the country and Icelandic farmers own more than 80% of the company. This is why textile artists who come to the center have trouble finding wool for their own crafts.

In the textile center’s lab, we learn about an interesting wool dyeing project which was a collaboration between the textile center, the marine biotechnology research center BioPol and the spinning mill Istex. The goal was to create a sustainable dyeing process for Icelandic wool with the purple dye produced by the bacterium Janthinobacterium lividum. The tests indicate that there is potential to scale up the production of the purple pigment called violacein. The next step would be to test quality of light and wash fastness of the dyed wool samples.

With different types of production chains, including China or not, the wool seems to have a higher status in industry and society in Iceland than it has in Finland. However, not even one of the local people we met were wearing wool. The students at our host organization, The Culinary Institute of Iceland, were dressed exactly like young people anywhere. Maybe it was still too warm, or maybe the sweaters are not worn at the office or in school.

Sweaters at the Handknitting Association store. Photo: Ulrika Dahlberg

Circular food production for the local community

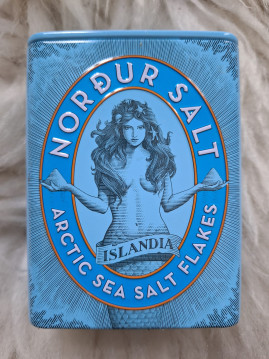

Also in food, the sheep are central, together with the wild landscapes and the sea. Lamb soup, fish, salt, wild herbs and seaweed are the things that stay in my mind as the core of the culinary traditions and product development. In many places you can for example find salt mixed with different spices and herbs, with names and brands that catch attention. The traditional dishes and artisan food products are well established, but the product with most potential for innovation could be seaweed, with possibilities to make protein-rich food, animal feed, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, fertilizer, biofuel and much more (see e.g. Isea).

When it comes to vegetables, Iceland is not even close to self-sufficient, we learn from Amber Monroe, who is running a small-scale aquaponic company, Ísponica, with a wonderful view in a village called Hofsós. Amber aims to produce microgreens and vegetables for the local community, by using nutrient-rich water from fish tanks. The water originates from mountain springs. In the system, the water flows from the fish tank to a biofilter, where nitrifying bacteria converts the wastewater into nutrients the plants can use. The water then flows to the shelves where the plants are growing. Here, the plants will take up nutrients from the wastewater. After the water passes through these, it is returned to the fish tank. The fact that similar systems or greenhouses for vegetable production are not more common in the country is somewhat surprising, since there is geothermal heat and power available.

Collaboration makes businesses stronger

Still, it seems that the networks around local food and textile production in Iceland are strong. People who work with food crafts and small-scale cultivation and processing know each other, trust each other and cooperate. The fact that small businesses can share resources, such as a kitchen with equipment for food processing at Vörusmiðjan in Skagaströnd, reduces the need for individual investments, supports the local community and contributes to a circular economy.

In conclusion, we have a lot to learn about branding, storytelling and collaboration from Iceland. In a few days, we didn’t have nearly enough time to see and learn everything we wanted to. For example, we heard that there is production of industrial fibre hemp in the east, and that the Westfjords are beautiful and special. And no, we didn’t try the fermented shark. That’s also something to do next time.

Sea salt flakes in an exciting package. Photo: Ulrika Dahlberg

The blogpost has been reviewed by Novia's editorial board and accepted for publication on 14.10.2024.![]()

Bioekonomi

Blogginlägg som är granskat av Novias redaktionsråd är utmärkta med nyckelordet "Granskat inlägg".

Vi följer CC-BY 4.0 om inget annat nämns.

Ansvarsfriskrivning: Författaren/författarna ansvarar för för fakta, möjlig utebliven information och innehållets korrekthet i bloggen. Texterna har genomgått en granskning, men de åsikter som uttrycks är författarens egna och återspeglar inte nödvändigtvis Yrkeshögskolan Novias ståndpunkter.

Disclaimer: The author(s) are responsible for the facts, any possible omissions, and the accuracy of the content in the blog.The texts have undergone a review, however, the opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Novia University of Applied Sciences.